A History of Cannabis in the United States

Anti-cannabis propaganda was popular in the 1930’s-1950’s.

As a wellness company, we at Proof know what a powerful and important plant cannabis is. We have created our company out of a mission to share that knowledge, and improve access to the benefits of this plant. It’s important to us, in this mission, to remember how we got to where we are today. The history of cannabis in the United States is complex and fraught with conflict. Understanding and learning from this history is crucial to moving our country, our industry, our company, and ourselves forward in the right direction. Without the historical context, we lack a fundamental understanding of who we are today, and how to conduct ourselves in our environment. So today, a brief history of Cannabis in the United States; please read and join us at the end, better equipped for tomorrow.

A hemp farmer in the late 1800’s.

1600s-1900s: Three Hundred Years of Hemp

As we have narrowed our focus to the United States, we start here around the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the founding of the United States as a nation. In these early days, the cultivation of hemp was not only allowed, it was greatly encouraged by the US Government, even required in some states. Hemp was also a legal tender in some states, such as Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Maryland.

Beyond hemp, cannabis was widely used in medications and sold by the ounce and pound without restrictions in pharmacies. The smoking of “hashish” had gained some modest popularity, but overall, cannabis was mostly consumed orally rather than smoked in this era. Suffice it to say, that for these three hundred or so years around the founding of the United States, there was nothing taboo about cannabis.

1900s: The Mexican Hypothesis

During and after the Mexican Revolution of 1910, there was a large increase in immigration of people from Mexico into the United States; many refugees fled the violence and large casualties of the nearly-decade long war in Mexico, and the instability of the regime changes during the time led many more to escape the region. The “Mexican Hypothesis” is a widely regurgitated theory that Mexicans were accustomed to using cannabis recreationally and frequently, much like people consumed alcohol in the United States, and that the widespread use of cannabis among mexican immigrants lead to the introduction of the smoking of cannabis in the United States. Thereafter, xenophobic and racist ideas associated the Mexican immigrants and their cannabis use with with crime, violence, and deviance.

The Mexican Hypothesis, however, doesn’t seem to be backed up by historical evidence. In fact, it appears that recreational cannabis use was as rare among Mexicans as it was amongst people in the United States at the time, and that the fear of cannabis causing violence and mania may even have originated from Mexican attitudes toward the plant, rather than being created in the United States as a response to Mexican cannabis use.

In a paper written by Isaac Campos, entitled “Mexicans and the origins of marijuana prohibition in the United States: a reassessment” these discrepancies are explored at length, and he offers a number of enlightened theories as to why the “Mexican Hypothesis” was created and has persisted. We highly recommend this paper to any history buffs out there, as we cannot begin to unpack it all here. All that said, the fact is that during this time, cannabis in the United States narrative transformed from a retail commodity that was neither greatly coveted nor scarce, into a dangerous drug that was infiltrating and corrupting the United States by violent and crazed Mexicans.

1930s: The Great Depression

During the economic downturn of the 20s and 30s, racism in the United States grew a different kind of edge. With unemployment increasing, poor whites seemed to be grasping at straws to maintain a feeling of superiority, and racial tensions surged. Veiled as “research,” studies began to correlate cannabis use (read; Mexican Americans) with violence, crime, and deviance. This provided groundwork for the banning of cannabis in the United states, with 29 states outlawing the substance by 1931.

1937: The Marijuana Tax Act

After decades of propaganda, and state-by-state outlawing of the plant, the federal government passed the “Marijuana Tax Act” in 1937, effectively criminalizing the possession of cannabis nationwide with the exception of possession of proof of excise tax being paid with specific medical or industrial purposes. This act is now considered to have arisen directly from the efforts of Harry Anslinger, the first commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. Throughout the 1930s, Anslinger propagated deadly myths surrounding cannabis and associated minorities, specifically black and latinx Americans, with the drug. He was openly racist, quoted saying in regards to Black Americans: “Reefer makes [redacted racial slur]s think they're as good as white men.”

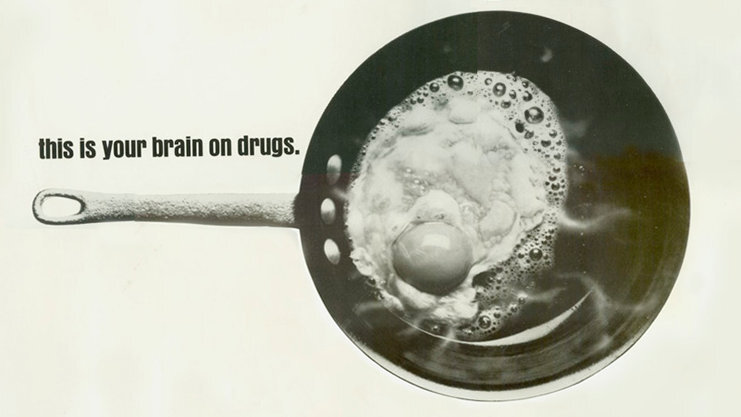

Anti-cannabis propaganda in film and media.

1940s-1950s: Contradictions Arise

In this period, while truth was coming to light about the nature of cannabis, laws continued to tighten their grip. In strict contrast to the pervasive propaganda of the last 50 years, the New York Academy of Medicine released a report in 1944 that found no correlation between cannabis use and violence, crime, addiction, or other drug use. Meanwhile, in the 1950s, two acts (Boggs Act, 1952; Narcotics Control Act, 1956) set stricter laws, introducing mandatory sentences and dictated that a first-offense marijuana possession carried a minimum sentence of 2-10 years with a fine of up to $20,000.

1960s: The Age of Aquarius

During the cultural revolution of the 1960s, cannabis became much more widely used among middle class white Americans, and as a result, public attitudes began to soften. The reasons for this are myriad; cannabis aligned with many new popular cultural explorations, including attempts to meld the racial, political, and economic divides in the country, psychedelic research, and Beat Generation literary movement; the overall shift was towards inclusion, discarding of inhibitions and fears, and with that, cannabis came back in a big way. With the more widespread and exposed cannabis use came the realization that cannabis did not cause violence as was once thought, and research began in the use of cannabis as medicine.

1970: The Controlled Substance Act

As a part of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, the Controlled Substance Act differentiated drugs into Schedule tiers based on their potential for abuse and addiction as well as their accepted medical use. These designations also defined their legality on a federal level, replacing the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 as the new means of cannabis prohibition. “Marijuana” was listed, and continues to be listed, as a Schedule I drug, denoting that:

“The drug or other substance has a high potential for abuse.

The drug or other substance has no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States. and,

There is a lack of accepted safety for use of the drug or other substance under medical supervision.”

Ironically, today Pure (–)-trans-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (or, THCΔ9, the most common psychoactive compound in recreational cannabis products) is also listed in Schedule III for limited uses, as a pharmaceutical drug under the trademark Marinol. This is a direct contradiction to the assertion that there is “no accepted medical use” for the Schedule I substance.

Anti-drug commercials in the 1980’s and 1990’s.

1970s and 1980s: The War on Drugs

Even before “War on Drugs” of the 1980s, there was a cultural war over where to place cannabis on the spectrum of good and evil. In the 1970s, parent groups who were concerned about cannabis use among teens began to gain power, and were eventually supported by the DEA (Drug Enforcement Agency, founded 1973) and the NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse), leading to a nationwide stage for their message. At the same time, individual states began loosening laws around cannabis possession and criminalization.

However, the anti-drug momentum backed by government agencies eventually led to Nixon’s 1980s “War on Drugs” mentality, which persists today as the United States spends billions of dollars annually on the enforcement of the Controlled Substance Act. Today, the US has the highest incarceration rate for drug-related crimes per capita in the world. Of those, black and latinx people are 2-4 times more likely to be incarcerated for drug related crimes than white people, despite consistent data showing that drug use is equal among these racial classifications.

1990s - The beginning of “legalization”

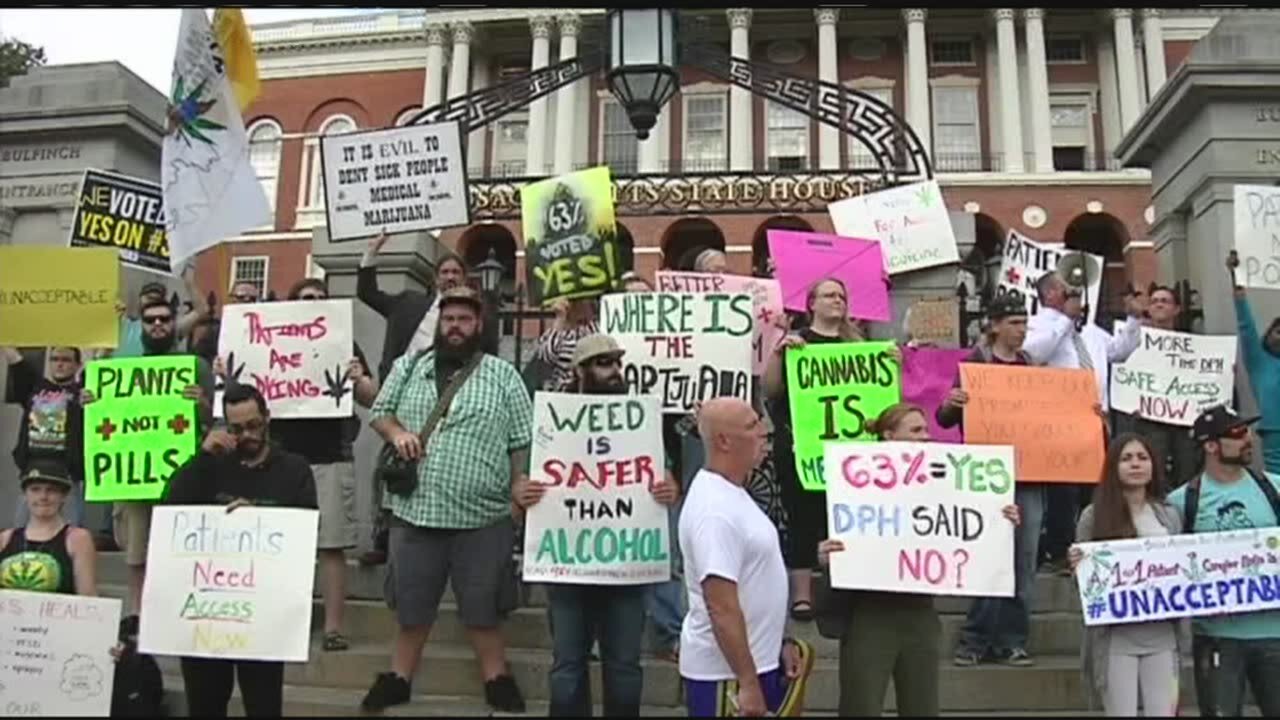

In 1996, in the first decision of its kind, California passed Proposition 215, which allowed for the sale and medical use of cannabis for patients with qualifying conditions. This law stood in contention with the federal law prohibiting cannabis possession. Four more states, Alaska, Oregon, Washington, and D.C., followed suit with medical marijuana legislation in 1998.

2000s to Today: The New Millenium

Despite the ripple of medical marijuana legislation that swept the nation in the 1990s and 2000s, federal restrictions have not budged. In 2012, Colorado became the first state to legalize the use of recreational cannabis as well, making cannabis “Fully Legal” for adults in the state of Colorado. Today, 12 states have fully legal cannabis programs, 28 have some sort of either medical or decriminalized status, and only 11 side with the federal ruling of “fully illegal.”

At Proof, we operate in the “legal” and regulated market in California, for both medical and recreational consumers. We operate in defiance of federal laws that list cannabis as a Schedule I drug with no accepted medical benefit. We operate in a fully open, state-recognized system that was created on the backs of the pioneers in our state who operated with the same passion and mission we do today, but who faced persecution for their pursuits on both a state and federal level. We thank all those who came before us and created our industry, and we hope to carry on the legacy, support and give back to those who continue to fight for their right to health and liberty.

Sources:

https://www.drugpolicy.org/sites/default/files/drug-war-mass-incarceration-and-race_01_18_0.pdf

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/dope/etc/cron.html

David E. Newton (2017). Marijuana: A Reference Handbook, 2nd Edition (Contemporary World Issues) 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. p. 183. ISBN 978-1440850516.

DATA SOURCES: NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURES, CNN, CONGRESS.GOV.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdfplus/10.1086/SHAD3201006